#GENDERFLUIDITY #CORRECTPRONOUNS #ITSALONGPOST #SORRYNOTSORRY

How do we continue to learn and grow as adults? In our age of self-care trends and polemic politics, this is a challenge I consider constantly, if only because stagnation means being left behind. How do I gain new knowledge? How can I keep up with new technologies? How do I get better? I don’t really have an easy answer but I do know that being uncomfortable is a good start. The sort of uncomfortable that comes with a conversation topic you know nothing about or the uncomfortable of new environments and new people. It gets harder to intentionally find those things as I get older, it’s much easier to construct and live in a safety bubble of work/home/husband/friends/family. ‘WHHFF’ for short. Woof, indeed. How lame. So in remedy to this, and partly because Michigan winters require cultural events with good people and booze, I went to an exhibition reception at the UICA where I ran into Gypsy Schindler, local artist and educator. We joked about how those type of events can often feel tedious but are so necessary for our artist-profession and we also talked about our work. Specifically, we discussed Gypsy’s work, portraits of people who embody a fluid quality within their identity. I left that conversation really curious to know more about her ideas and process partially because the concept of fluidity in terms of gender, sexuality, race, age etc is really interesting but also because it’s a topic with which I need more experience. I haven’t mastered all the words to talk with confidence about LGBTQ culture, I’m a straight white woman, and I need more conversations about this to feel comfortable and knowledgeable in that sphere.

So I followed up with a studio visit to Gypsy’s home.

She lives in a very cute Heritage Hill style apartment with hard wood floors, high ceilings and lots of light. She explained that the place belongs to her Aunt and Uncle who spend more of their time traveling in the winter, making it the perfect place for Gypsy to consider ideas of fluidity and transience. I always find it really easy to talk to Gypsy; she’s super smart, has lots of interests, openly shares thoughts and ideas, and is quick to laugh. I was counting on this when I set up the visit, typically I send my interviewees lots of questions and stick to them, but with Gypsy I sent just a few, I wanted a more meandering conversation.

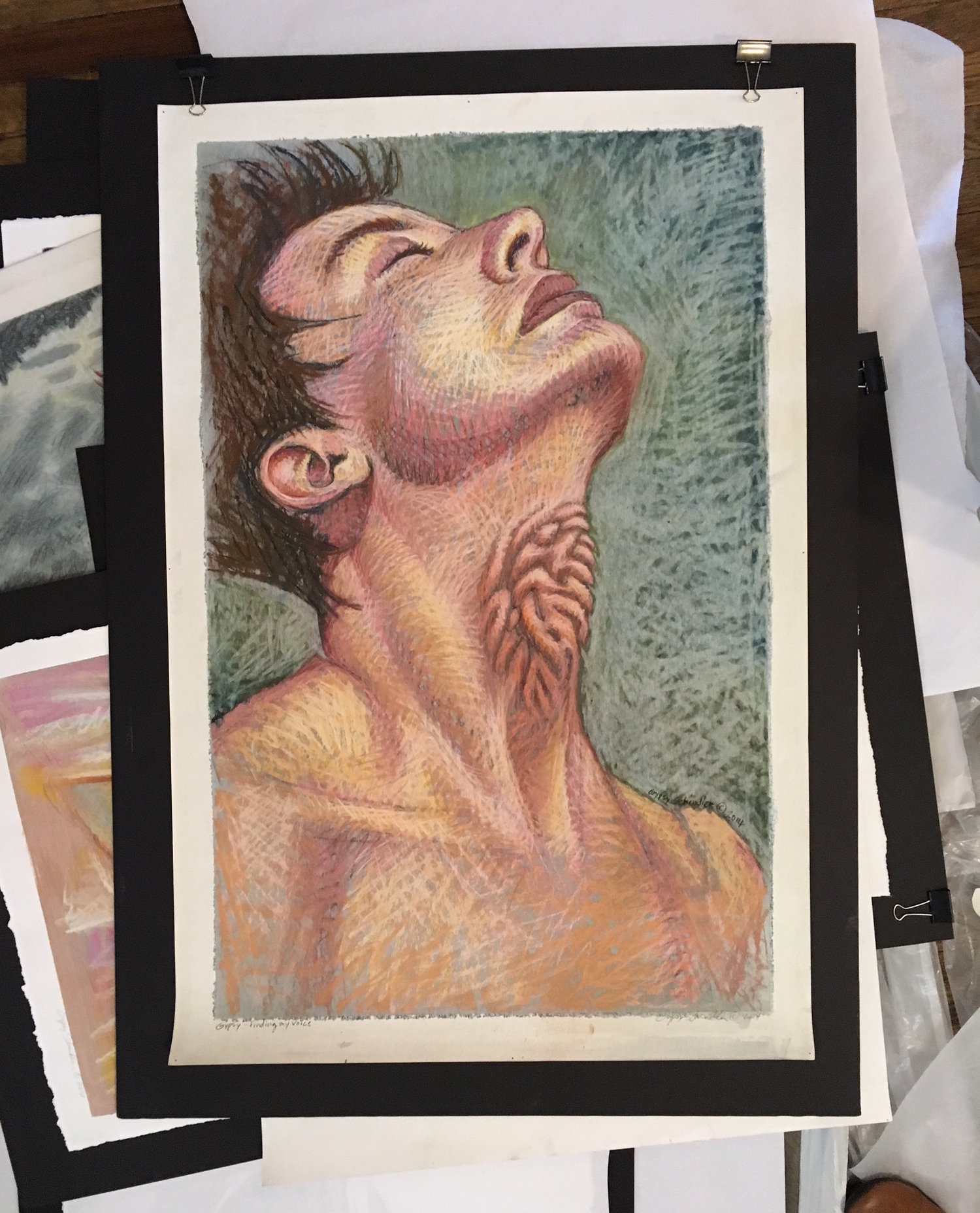

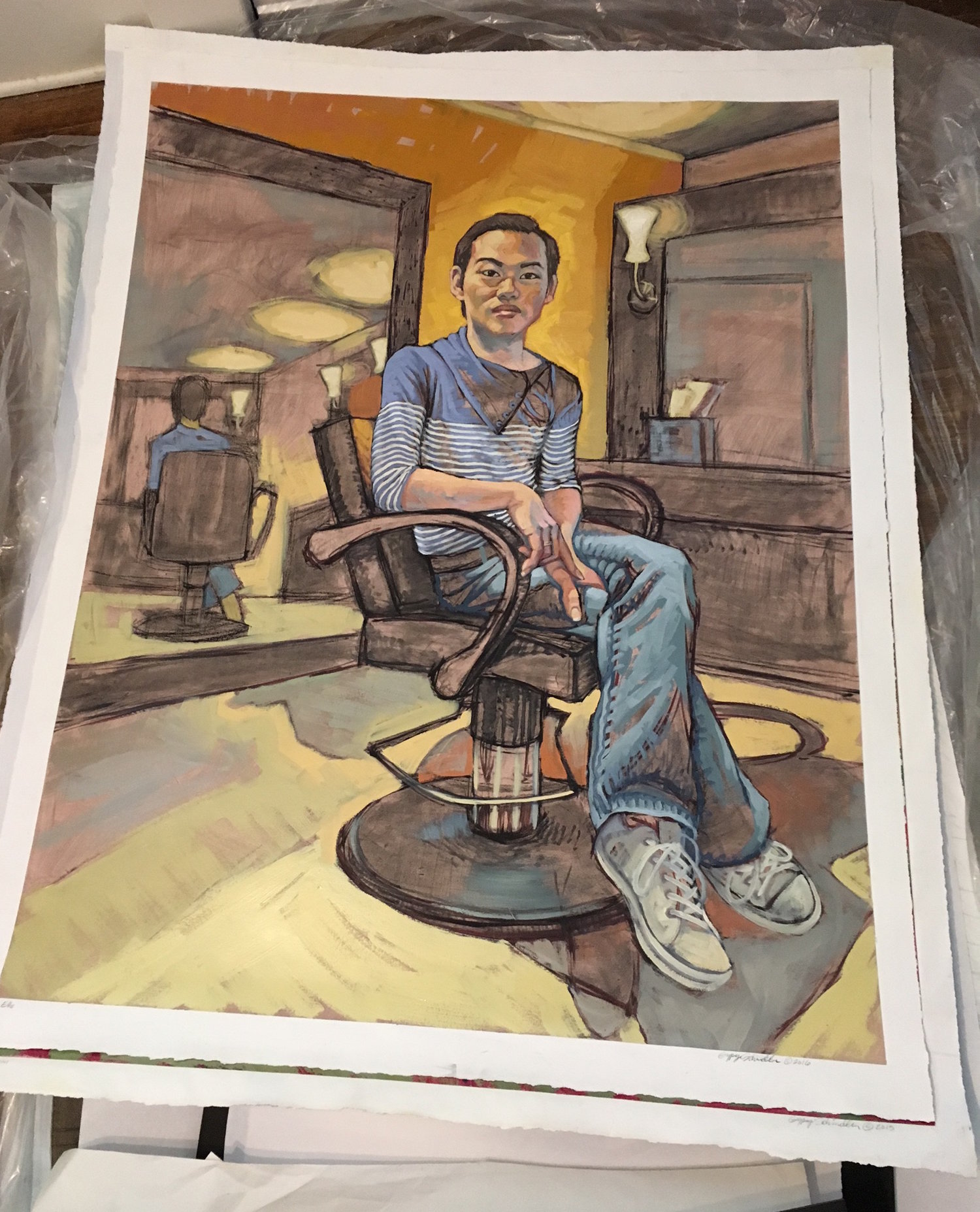

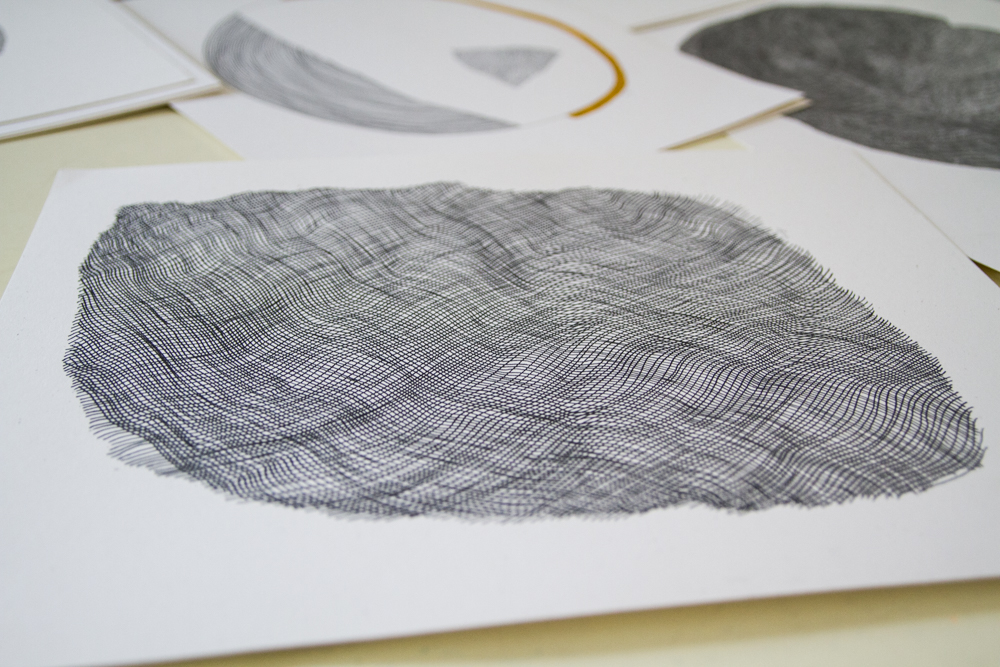

We started at the beginning, I asked about her training as an artist. She describes a childhood filled with books and drawing, filling her childhood home with projects that her mom still hangs onto; think treasured Christmas tree ornaments that are clearly the work of a five year old. We talked about her time as an undergraduate student at Kendall College of Art & Design, lots of figure drawing classes and her time in graduate school at Eastern Michigan University under the tutelage of Margaret Davis who “really taught [her] how to paint.” There she refined color theory, expressive brushwork, and explored printmaking. Her apartment is currently covered with a smattering of monochromatic monotype portraits of varying sizes. Gypsy describes how, for her, “monotypes embody both drawing and painting. It’s sculptural,” the way she uses brushes to almost carve away details from the ink-covered plexi surface before sending it through the press. But there’s so much more in these faces beyond the expressive marks that articulate their surfaces. I ask Gypsy to set up my understanding of her current work by talking me through older bodies of work.

“Describe the last formal body of work you completed.”

“Her response is telling, “What do you mean by formal body of work?”

So I rephrase, “Tell me about a recent body of work that you worked on for a significant period of time… maybe a grouping of pieces that come from a single place… in iteration… or maybe you don’t even work like that and it’s more of an on-going flow of work for you.”

“Well, the body of work I’m working on right now, visually, probably looks the most like a series. It’s all portraiture. It’s a little more simple… a little more direct in its presentation… The series that I did before… I’m right in the [middle of] ‘before-and-after’… in the ‘before’ there were multiple [series] going on at one time… my mind was so scattered and I didn’t know where I wanted to focus my attention… so I did a series about memory, and then about family structure, then a series about self-definition within the family structure... I did the family portrait series and then stopped when my own family fell apart and I went back to self-portraiture. I always return to self-portraiture when I don’t know what else to do.”

“Why do you think that is?”

“Oh my goodness, um… because it’s an immediate break of artist block. You have no excuse to not do a self-portrait. And self-portraits are so revealing. Every time I do one I look so different. My first body of work was pretty much a huge freakin self-portrait. I did some intense therapy for about 15 years and worked through a whole lot of shit… read every self-help book… and so I can see my evolution in my self-portraits. I’d love to do a self-portrait exhibition someday.”

I agree whole heartedly to this notion.

“Right, I mean, one gets older (chuckle, chuckle) but also my posture changes, my presentation of myself changes, the way I hold myself changes, everything changes. Through my self-portraits I was… oh, how to simply put it (?)… [learning] how to value myself, and how to see myself past all the judgements that I’ve had about myself, for years. And I’m still learning to see myself past all the judgements that other people have about me. In the ‘before’ [I was] doing self-portraits while holding all those self judgements in front of me and not understanding how to care for myself and love myself. The more you do that the more deeply you can connect with other people.”

“I like calling it that, the ‘before.’ Do you think you were aware of all of that while it was going on? Or is it just now, in the present that you’re able to look back and articulate all of that?”

“I think both… I was aware of it, ‘cause I was in therapy. [But] you have to let yourself fall apart to put yourself back together. And so I let myself fall apart. I wasn’t [living] in the present because I was holding all of that awareness in front of me all the time, I couldn’t just relax and therefore I was really numb. A lot of my work was really numb.”

“How does that translate visually?”

“Detached. If the figure was addressing the viewer it was very stoic and stone faced, or aggressive and defensive, or the figure wasn’t addressing the viewer. And now, all of my faces look right at the viewer and are pretty naked, emotionally. So that’s me ‘before,’ and me ‘after’ just feels naked, all time!”

We laugh. “That’s a terrifying prospect!” I chime in.

“It is, but it’s better. Ya know.”

“Freeing?”

“It’s more alive. It’s not freeing. Are we ever free?”

“That’s a deeper philosophical question,” I suggest.

She claims she’s full of those (deeper philosophical questions) and chuckles, “But, ya know, in the last two years I’ve experienced more pain that I ever have, but at least I know I’m here. And I’m okay with that. I’d rather have the naked than the numb.”

“What a great line,” I say. At this point, dear reader, you’re probably thinking, ‘this is getting pretty personal.’ Don’t worry, I asked Gypsy how much she’s comfortable with me sharing.

Her answer: “All of it, go ahead.”

Lately she’s started writing poetry, and believes that writing and sharing is so important. “Words are so visual and metaphorical. For me, [words and images] are much the same.” She reads to her students at KCAD and Hope College in Holland in the drawing classes she teaches, all sorts of work from the serious literature of Dillon Thomas, to the poignant prose of Iggy Azalea (Fancy, if you’re curious).

Turning back to her work, I ask, “So the ‘present’, still primarily self-portraits?”

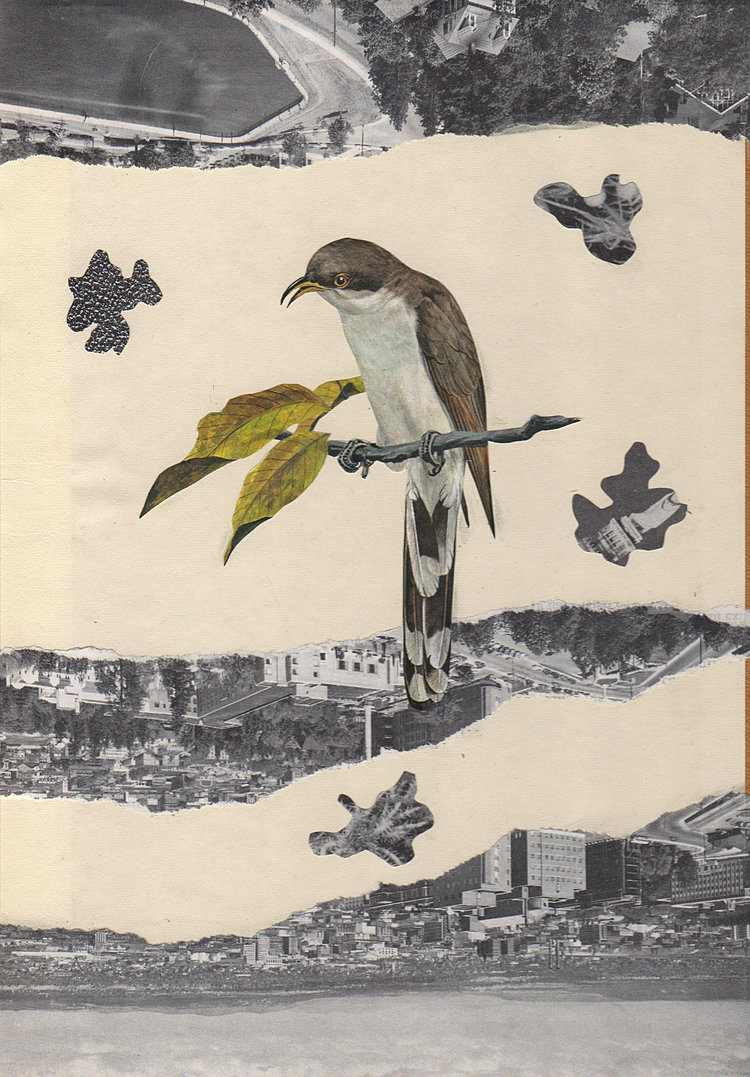

We move over to a big pile of large scale drawings in a variety of media. The answer is no, only sometimes, every once in awhile, if she needs to test out a new size or process. But recently, she’s been drawing other people, people she knows, people with whom she’s acquainted; her hair dresser, a gallery guard she met during ArtPrize, one of her students, a friend’s son, still more of her family. Most of these people share a subtle quality of identify fluidity.

“I’m sort of an incessant reader of existential thinkers; Eackhart Tolle, Michael Bernard Beckwith. Right now I’m listening to this guy called Kyle Cease, he’s a former stand-up comedian turned existential thinker.”

“Whoa.”

“He’s talking about fluidity in terms of how you become comfortable with the unknown and the uncomfortable.” She takes a big, deep breath, “Which I think applies to my whole life right now. I get mistaken for a man a lot, or I get taken for transgendered… a lot. And so within my portraits there is fluidity of gender.”

I look at the portraits she’s unveiling from a large pile, one of a young girl(?) on a stool is striking. Their eyes follow me even as the drawing is shifted away.

“It’s interesting because that doesn’t have anything to do with me, that has to do with how someone else sees me. That’s just one of the ways that I see how I’m perceived as fluid from the outside and I feel like I’m completely fluid all the time on the inside. There are so many different ways I perceive other people as fluid and it comes across in my work… of race, culture, age, even just in someone’s facial features.” She points to a portrait of her brother, “I made him look like a Jewish rabbi,” she laughs, “and he’s like the whitest hillbilly boy ever.”

In some works, the sitter is larger than life size in the frame and takes up most of the paper leaving little room for environmental queues. In others, the sitter is depicted full body in a nondescript space. We discuss how, within a conversation, beyond sharing words and ideas, two people also try to interpret each other’s facial expressions, tone of voice, speech pattern, eye contact, etc to the point where they’re not listening, not really, to what the other person is saying, and not really looking, they’re just running those visual and auditory queues through signifying filters that have been built up over time to quicken the comprehension process. Gypsy suggests that a portrait, a static portrait allows us to quiet that filtering process, and better see the person, to not assess or evaluate, but really see them without our guard up. It’s intimate. We hold no pretense of expecting return. We judge less. Instead, looking a portrait, you can wonder, ‘who is this person?’, without labeling them based on a fraction of an interaction.

Gypsy hates the word ‘should.’ She says, “There’s only what you will and what you won’t. If we only took people a little more fluidly and allowed them to, I don’t know…”

“To be. To just exist in whatever state they happen to be in at that moment…”

“Yeah… stop protecting your self so damn much,” she says as if reminding herself. “I’ve learned that.”

We look through more of her work, talk about the proper use of pronouns and admitting when you don’t know something. Another portrait of her brother floats by, I think about how natural it feels to understand the world through categories. Everything and everyone must belong to a category; if it’s not this then it’s that, binary systems. A trio of mystery faces are laid side-by-side, I think about how limiting those are systems are and how beautiful the undefined can be.

As we continue to talk about uncomfortable situations and the sometimes hard-won lessons that come with them, I make an analogy about being in the ocean. It’s like standing in the shallows before you’ve gone all the way under, watching a huge wave slowly build and roll toward you, you know it’s going to be cold but you can’t stop it, slow it down, or get away. You just have to brace yourself and let it pass.