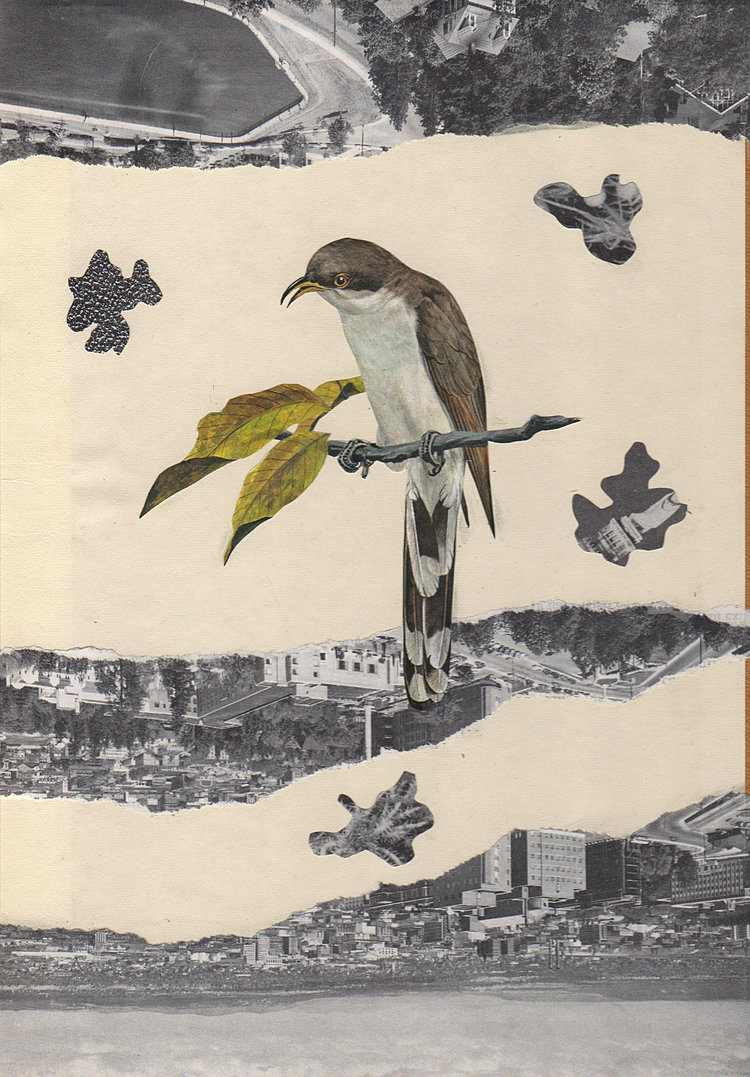

#COLLAGE #RYANWYRICK #INTUITIVEART #FOUNDIMAGES

How often do you look at a piece of artwork and feel affection toward it, without any need to interpret or infer a deeper meaning beyond the shapes, colors, and lines of the work? I’m talking about a purely aesthetic moment void of psychological rationale, the kind of moment that arrests you within the daily grind and forces you to pause and simply look. Over the next few months I will present interviews with artists whose works have this effect on me. To start, I paid a visit to Ryan Wyrick, Grand Rapids collage artist in his home-studio. Ryan lives above a gallery on the Avenue for the Arts in a beautiful historical building with high ceilings, pocket doors, and sky lights. You may have met Ryan along the Avenue during a Market event where he was selling handmade blank books or at a DAAC show when they were still on South D, but I am most interested in his collage work. He rarely exhibits but shares via Facebook regularly and I’ve been admiring him from a distance for months.

Ryan grew up in Wyoming, MI, a suburb of GR and he became interested in the Avenue for the Arts corridor while still in high school.

“The UICA was really the first institution I’d ever been in in this area, when I was like 16 and didn’t know anything about the realm of downtown... it was actually for Live Coverage… it was incredible, it was a bunch of weirdo artists making on-the-spot and it was magic.”

He then discovered the DAAC, attended all-age music shows, and the Avenue for the Arts, where he began vending during the Markets in the summer. As we talk he sort of marvels at how this trajectory landed him into the space he currently occupies; a resident and maker on the Avenue who participates in the organization’s neighborhood revitalization efforts and recently exhibited his own work at the UICA.

When I reach out to artists like Ryan I also provide a list of questions about their practice and process. I do this for two reasons, first, so they have time to form clear thoughts ahead of my visit and second, so I keep myself on-track during our conversation. It’s incredibly easy to get distracted and wind-up talking about old magazines for an entire hour or mutual artist loves. This was completely true with Ryan who is kind and open about his thoughts. So to kick it off, I asked him to describe his work as if he were speaking so someone who’s never seen it.

“It’s collage-based work with paper and sometimes found objects!” He says in an overly animated voice, then sighs. “It’s really hard to describe… the more that I make collage work the more difficult it becomes [to describe]. When I first started it was very easy; [I’d say] ‘I cut out animal illustrations from encyclopedias… then I put captions with them and they say things and it’s fun and bright.’ But now it’s more difficult because a lot of the work varies so much… beyond saying that I make work with paper and found objects and that a lot of it is slightly abstract, it’s really hard to delve into it without talking about it for an hour.”

One of the reasons I like to ask that question of all artists is because I want to get the language right. There is a certain action and power associated with a word likeappropriation, which could apply to the collage processes, but in Ryan’s case he’s less interested in that type of direct statement or controversial reclamation of a commercially printed image. Instead, he works intuitively, he starts by physically cutting out shapes, arranging them together and then rearranging.

I ask, “When you’re in the middle of making one of these, what helps you to make choices about these shapes and colors and placements?”

He considers this for a moment and says, “It really just depends on the piece. Some of [the shapes] are just scraps, the result of cutting another shape. Where they get placed...” he thinks for a moment, “sometimes things just click and they feel right, I think that’s the closest I can get to explaining it. Some of them I can get done in an hour and they feel perfect, some of them I have to rework four or five times and they become something completely different, others I just have to shift a piece of paper or replace it.”

I’ve been looking at Ryan’s work along with a handful of other artists who have developed a highly recognizable abstract style and thinking about how their work fits into a semiotic model; how they generate a vocabulary of lines, shapes, and colors and create compositions that almost constitute a unique language. However, after talking with Ryan and looking at a large number of his works at once, I began to think that instead of a solid language or a consciously constructed alphabet, his work feels more like a conversation of gestures between two people who may not speak the same language. He feels his way through each piece through trial and error.

I explain all this to Ryan and he agrees, “I think that resembles my process a lot more than a concrete form of communication.”

We move on to discussing his materials choices, specifically book covers. He’s been using these as his primary substrate lately and I asked why, “I think that the main reason is that I’ve been given a lot of books and they’re free, but also because once you cut something out, like from an encyclopedia, it becomes valueless. So once you’re done with the images what happens to that book? You can discard it, but why not use the covers. It just makes sense for me to use it all. It also forces me to make it work in a certain fashion.” He points to a piece in front of us that primarily features black and white imagery. “This one is pretty much a black and white image because the background paper of the book is grey. And these,” he points to another of mostly browns and neutral tones, “work well for this brownish background. The covers determine the palette.”

“You’re not having to start with a blank white sheet of paper,” I observe.

“Right.”

We continue to talk through some of his compositional choices and problem solving techniques and eventually I ask about his influences and other artists whose work he admires. One of his catalysts is the Dada movement of the early 1900s, specifically because of those artists’ use of commercial materials and sometimes absurdist constructions. Also important, is the notion of anti-art in general, Ryan embraces the idea that there are no rules in making art and that a personal, intuitive approach is the most appropriate for his work. He also cites the artist Holly Chastain as an admirable influencer. Looking through Chastain’s website, I see an obvious connection between her work and Ryan’s. One of the distinguishing differences is evident in Ryan’s most recent work where he incorporates found objects, three-dimensional items into the compositions. I ask him about these pieces.

“A lot of those found objects are found on the side of the road or found on the sidewalk, so a lot of the rules are broken, like ‘what can be used in a collage?’” he explains.

“You’re making something really common into something precious.”

“Yeah, I guess any artists uses that, right, you’re taking something that has no value... no use, like this,” he points to a bit of smashed and rusted metal in the center of one of his works, “there’s no use for a gross, rusty whatever that is... it’ll eventually get knocked into the sewer and end up who knows where... but anytime you use an object like that, like Tom (Duimstra), [another Grand Rapids artist] most of his work is just random stuff that he finds and now [as a sculpture] the intended object is pointless but he brings value to those things. I think that’s just an inherent trait when you start using something as a tool or media for art… it has an increased and inherent value [as the art object].”

“Then the question becomes ‘why?’” Why did the artist choose these colors and these shapes?”

“For me, I think I use a lot of neutral tones and patterns because I use a lot of found materials like security envelopes and old book pages that have this nice tan tone. And from there it’s about whatever paper will add some vibrancy. I can’t say I have an actual color palette, the pages that I find in the books dictate the color, it’s not like paint where I can choose whatever color I want. It’s not as fluid and loose as other media... sometimes the colors choose me because of some other quality.”

We spend the next half hour or so looking through a large number of his works and Ryan talks me through his experience making each one. Often he describs small decisions that led to bigger challenges, like the selection and cutting out of a house that proved difficult to pair with a background. I keep thinking about how measured and methodical his process sounded while also retaining the intuitive fluidity he had described earlier. I believe that he’s achieved a delicate balance of the two where the final product feels cohesive, a little mysterious, and very specifically a Ryan Wyrick creation.

I know I spend a little more time looking at his work each time it crossed my path and now, with these insights, I may look even longer.